Feeding Little and Often – ignore it at your horse’s peril…

We all feed our horses to ensure they get the right nutrients for work and health and we’ve all heard that we should feed ‘little and often’… but just how little is little and just how often is often?!

‘Little and often’ has long been one of the golden rules of feeding horses. And with good reason because feeding large, infrequent meals conflicts with how the horse has evolved to eat.

But why the confliction?

Well, to understand this fundamental horsey question, we need to look at how our horses have evolved and what happens when we feed them large, infrequent meals and decide to ignore the ‘little and often’ approach.

Does meal size and frequency matter?

If you’re a horse, yes!

Horses are non-ruminant herbivores and have evolved to graze continuously on fibrous plant material, for as much as 18-20 hours per day!

If you’ve ever watched your own horse in the field, they tend to take in small amounts of grass with each bite then chew, moving on to a different patch after a few bites and so on. Eating in this way has led to them being known as ‘trickle’ feeders, and this means that the feed they ingest (technically termed the ‘bolus’) together with saliva from chewing, pass into the stomach in a constant, small trickle.

Little and often works well with the digestive tract

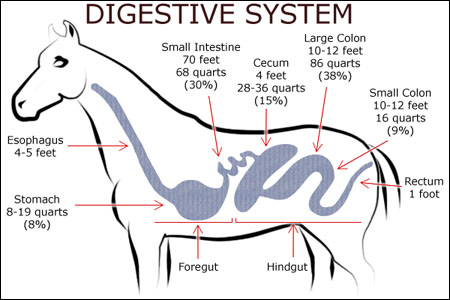

The horse’s stomach is small – just about the size of rugby ball – with a limited capacity of 9-15 litres and comprises just 10% of the digestive system. The stomach uses both acid and enzymes to start digestion and this works far more efficiently if your horse’s meal size is kept small.

To accommodate a constant, small trickle of food, the horse’s stomach empties regularly, moving the bolus on to the small intestine for enzymatic digestion.

The small intestine is relatively short and although it produces enzymes to digest feed it has a limited ability to digest starch, with a rapid transit time (about 1 ½ h), meaning feed moves through it quickly. However, when there is a small trickle of feed flowing through it on a little and often basis, digestion and absorption of nutrients in the small intestine is surprisingly efficient!

In the large intestine or ‘hindgut’ (caecum and colon), food is broken down by fermentation by a large and diverse population of microbes. A constant trickle of fibrous feed into the caecum means it gradually fills and when full it triggers the release of small amounts on into the colon for further microbial fermentation, squeezed out of the caecum like toothpaste! Rather than eating until their stomach is full, horses need to eat small amounts continually until their caecum is full, to ensure optimum hindgut function and fermentation, so eating little and often is the way to go!

Small and frequent meals promote healthy digestion

The horse’s digestive system has evolved to digest starch and sugars in the small intestine rather than being fermented in the hindgut. Small, frequent meals support this, leaving the fibrous fraction of the meal to be fermented in the same way that the fibre in grass or hay is. A continuous, small flow of feed through the digestive system also keeps it functioning and working efficiently.

So, we know that feeding little and often supports the way horses have evolved, but what happens when we ignore this and feed large, infrequent meals and why isn’t this ideal?

Do large, infrequent meals make a difference?

Yes! Less frequent meals of more than 2-2.5kg per meal for a 400-500kg horse or >2g starch per kg Bodyweight (BW) per meal have the potential to cause problems…including:

Gastric ulcers

Unlike us humans, horses produce stomach acid constantly, even when the stomach is empty. When a horse eats continually, i.e. little and often, chewing produces a consistent volume of saliva to help buffer stomach acid. This helps prevent ulcers forming in the upper (squamous) area which has no mucus layer to protect its lining. Infrequent feeding means no saliva is produced when the horse is not eating, leaving this area vulnerable to acid penetration which can lead to gastric ulcers.

Although digestion in the stomach is primarily through gastric acidic and enzymes, small amounts of microbial fermentation of starch and sugars taking place in the squamous part of the stomach is normal due to the presence of certain types of microbes. When a large meal is fed, however, this fermentation can rapidly increase and get out of hand. Lactic acid produced from excessive microbial fermentation means the squamous section becomes strongly acidic, leaving the lining vulnerable to ulcers.

Laminitis

Quicker stomach emptying associated with large meals has a knock-on effect to the small intestine, meaning a relatively large feed bolus will travel through quickly and overwhelm it, leading to poor digestion and the potential for undigested starch to reach the hindgut. If starch reaches the hindgut it gets fermented by certain microbes to lactic acid. causing a drop in hindgut pH and a potential state of hindgut acidosis.

Acidosis can lead to a cascade of events including the growth of less desirable microbes, death of microbes who release certain toxic compounds, damage to the lining of the hindgut allowing for absorption of these compounds and ultimately, laminitis.

Research has indicated that larger, starchy, less frequent meals result in a higher glycaemic response¹. The glycaemic response is the level of increase of blood glucose following a meal and when blood glucose rises so does insulin to encourage tissues to uptake the glucose. Glucose ‘spikes’ from feeding one or two large meals per day means extra insulin will be released which may eventually lead to insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia (increased insulin in the blood). Hyperinsulinaemia is a risk for laminitis.

Colic

Large meals have a higher dry matter (DM) content which results in slower and reduced mixing of the feed with digestive juices. This decreased mixing can result in dysfermentation in that microbial fermentation that should have ended continues in the lower part of the stomach. Dysfermentation results in a build-up of gas and too much gas can cause colic.

Gut motility is enhanced when there is a constant trickle of food going through the gut. Infrequent feeding and large cereal based meals decrease gut mobility whilst producing fluid changes in the hindgut that can dehydrate the feed. Both scenarios will increase the potential for certain types of colic.

Additionally, hindgut acidosis from feeding large meals where undigested starch reaches the hindgut can also cause colic.

Meal feeding imbalances

When large meals of cereal grains or pellets are fed infrequently fluid shifts can lead to a decrease in circulating blood volume or hypovolaemia. Research has shown that this doesn’t happen when small, frequent meals are fed².

Large microbial fluctuations associated with large, infrequent meals can result in changes to the microbial populations which can compromise digestive health. Very recent research has demonstrated that feeding small meals three times per day resulted in a more stable microbial population compared to when larger less frequent meals were fed³.

Poor Digestion

Large meals are not digested as well as small meals, so If you are looking to add condition to your horse or pony, feeding larger meals is not the answer. Alternatively, feeding small more frequent meals is a much more effective way of building condition. Long gone are the days when you should proudly state that ‘he gets a full bucket of hard feed every day!’

Behavioural Issues

Feeding larger meals can result in fizzy or excitable behaviour due to the increased glycaemic response. If your horse is prone to excitable behaviour, feeding little and often should help curb it.

Infrequent feeding can cause stress and a build-up of stomach acid which can cause discomfort. Both these factors can lead to oral stereotypical behaviours, such as crib biting, which horses use as a coping mechanism. Some research has shown that offering stabled horses smaller, more frequent meals, significantly decreased crib biting⁴ so consider this if your horse crib-bites.

Little and often feeding tips

So, all things considered it’s easy to see why feeding little and often is so important for optimum equine health. The closer a feeding regime can get to this, the less potential for problems, so consider these essential tips:

- Provide plenty of ad-lib forage to ensure the stomach is never empty

- Feed by weight not volume – different feeds weigh different amounts

- Split the horses daily ration into as many small feeds as possible, ideally 3-4 or more.

- Consider increasing the energy density rather than the volume of feed by adding oil for example.

- Keep starch to a minimum and only feed what is needed for the horse’s work in small, regular meals.

- Never starve a horse in a bid to lose weight, instead offer feed that is low in sugar, starch and energy and high in fibre.

References

- Harris, P. and Geor, R.J. (2009) Primer on Dietary Carbohydrates and Utility of the Glycemic Index in Equine Nutrition. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 25 (1), pp. 23-37.

- Harris, P.A. and Arkell, K. (2005) How Understanding the Digestive Process can help Minimise Digestive Disturbances Due to Diet and Feeding Management. In: Equine Nutrition for All, 1st BEVA & Waltham Nutrition Symposia, pp. 9-14.

- Venable, E.B., Fenton, K.A., Braner, V.M., Reddington, C.E., Halpin, M.J., Heitz, S.A., Francis, J.M., Gulson, N.A., Goyer, C.L., Bland, S.D., Cross, T.L., Holscher, H.D. and Swanson, K. (2017) Effects of Feeding Management on the Equine Cecal Microbiota. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 49, pp. 113-121.

- 4. Cooper, J.J., McCall, N., Johnson, S. and Davidson, H.P.B. (2005) The short-term effects of increasing meal frequency on stereotypic behaviour of stabled horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 90, pp. 351-364.

This Post Has 0 Comments